Sid Wilson Discusses the Past, Present and Future of Slipknot

Earlier this month, Slipknot marked the 10th anniversary of their brutal audio assault ‘Iowa’ with a deluxe reissue of the 2001 album. The revolutionary disc took metal in whole new direction orchestrated by nine masked mad men. The album served as a turning point for the band, one where they proved that from here on out they would only be making music one way – their way!

A decade later, that cloak of darkness surrounding ‘Iowa’ is as heavy as ever. The statement the band left with ‘Iowa’ was a long-lasting one and on the 10th anniversary of the metal masterpiece the band is offering up a new anniversary edition full of extras including a live DVD and a new film titled 'Goat' directed by the group's own M. Shawn 'Clown' Crahan.

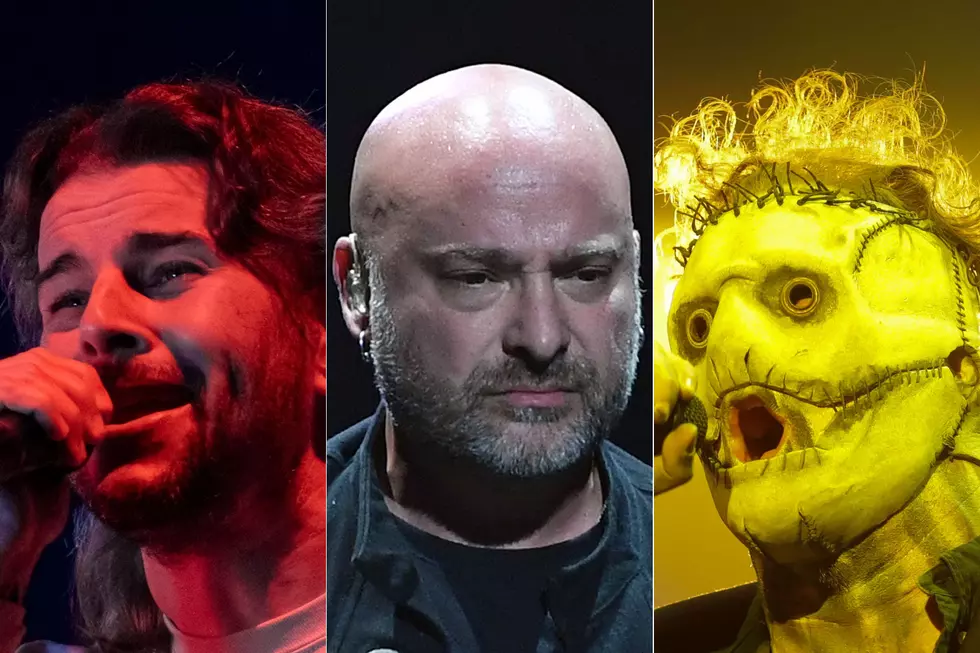

We recently had the opportunity to talk to the 'Knot DJ Sid Wilson about the making of ‘Iowa,’ the tumultuous band relationships during that time, the inherent power behind his mask and of course, the late Paul Gray.

Many bands celebrate their debut album, but Slipknot has chosen to honor their second release ‘Iowa’– that must say a lot about what the album means to you and how it’s impacted fans?

I think it’s just because it such a brutal album in terms of metal. Nowadays, a lot of hardcore metal fans listen to Slayer and Metallica, and nothing else. Iowa was a proving point for us. We weren’t just some new genre that you might want to tag us as, we are a metal band.

The song ‘Spit It Out’ on our first album was kind of a middle finger to the industry; ‘Iowa’ was kind of like a whole album of middle fingers. For the follow up album, the label and other people involved were pressuring us to do things more melodically but we were like "Don’t we get a say in this? You’re just going to tell us what you want us to do? Last time I checked we’re the artists, we’re the ones creating it, it’s coming out of our minds, not yours." A lot of these people weren’t even in bands so where do they get off telling us how to create our art. It was kind of just like they were hoping we’d write something more mainstream and more radio friendly, but we were like ‘no.’

It also says a lot about the mentality of the people from Iowa. Iowa has a hard work ethic and people really go out of their way to do things themselves and build it from the ground up. The minute that you try to tell someone in Iowa how to do something that have pretty much already been doing their whole life, and are professional at, and someone outside of that specific thing, that wasn’t around for any of it, tries to tell you how to do it, you’re just kind of like “You don’t know what you’re talking about, when we do this, we do it right.” It says a lot about the Iowa work force.

Thinking back to the time when you guys were making that album, it’s often referred to as a dark time for the band.

I wouldn’t say that it was the darkest period, we’ve definitely had darker periods since then but I think it was the beginning of the darkness for the band. For the first album, we were all together 24 hours a day and on the second album we were very spread apart. We were all staying in separate apartments, we wouldn’t see each other until we got to the studio, and after the studio time everyone would go to different places and go out on the town and hang out with different groups of people.

Where on the first album, we’d all go out and hang out together as a crew; we were like a gang almost. If there was a concert in town we’d all go together, we went and saw Fantomas play their first show in LA, the whole band went together, everywhere we went we wanted to be seen as a group, as a family, and that all just started to disappear on the ‘Iowa’ album cycle. I guess that was the beginning of the dark period. Seeing that a lot of us knew it was going to get darker from that point, we weren’t numb to it yet, and that’s why it ended up being so aggressive, so dark and so crazy.

Corey Taylor has referred to ‘Iowa’ as “The only album I’ve ever heard that you can wear like a skin.” He said that everything you were feeling at that time went into the album -- do you agree with that?

Yes, absolutely, the ‘(515)’ intro at the beginning, definitely speaks to that. Back then we would write stuff together, but as far as the recording process, I would play my scratch tracks in the beginning (scratch tracks meaning not just scratching DJ but like the temporary – when you record you try to capture the drums first – but then everyone else will record with the drums and you have kind of these temporary recordings that you can either keep or replace later). So, I would come back in at the end, after everyone had laid their stuff down, and create this mesh, and make sure I could carefully place anything just in case I felt there was a spot where I wanted to lift up so I wasn’t covering up a vocal, or if I could add something to what someone else was doing, or add to it.

My family is from England, I’m a first generation, so I’m the first in my family born in the states. My grandfather got really sick and it was right at the end of the recording cycle, there were only like 2 or 3 days left so I was planning to get my parts done quick and then fly out immediately to see him, he was in the hospital. It got up to the last day in the studio and he passed away. I didn’t make it out there, needless to say. I went into the studio, you can also hear some of this in our ‘People=S--t’ song, there’s a bunch of us doing gang vocals, which I did after this next part, but I went into the studio and was like ‘Turn it on, turn this s--t on and record.’ There wasn’t any music or anything, I just went in and let it all go.

You let all your emotions out?

Yeah, that screaming and crying and breaking down that you hear at the beginning of the album, that’s me. Obviously, it was edited, things were done to it, reversed, pushed around in areas, to make it what it was but we if we actually played just the raw recording of it, I don’t think many people would be able to stomach it. It was pretty brutal, but that’s all I’ve ever known how to do, express myself through music and art. I could get it out without just wanting to destroy everything. I didn’t know whether it was going to be used or not, that didn’t even matter. The intention wasn’t for it to be used on the album; it was just so that I could get it out of my system. Everyone in the studio was balling with me, and I just let it rip.

Speaking of letting it rip, you are a force onstage. We talked about your stage-diving and crowd surfing; what brings that out of you, is it the adrenaline of the show?

Yeah it’s the adrenaline, it’s the kids, and it’s a lot of things -- living in the moment. That outfit and that mask, especially the first gas mask, there’s something special about that guy. I talk about him like he’s somebody else because he is somebody else.

I was going to say, isn’t that you we’re talking about?

Nah, not really, I was never in my right mind to try to do some of those things. Those certain masks, there’s certain ones, I make sure to get ones that are out of World Wars that have been used in battle and that have been used in combat. Ones that have an energy inside them and possibly spirits around inside them that are following with me and helping defend me as I do it. This whole Sonisphere tour that we just did throughout Europe, I had an old WWII gas mask and there’s definitely some spirits in that following me around.

I talked to Paul [Gray] every day before the show, and pray to Paul, and ask him to help me and protect me as I go through with coming out of this retirement of stage-diving and go for it again at the age of 34. After this tour, it was so brutal on my body, I think I had a total of 32 cortisone shots over the period of four to five weeks, in my back and in my shoulders, just to recover from all of it, all kinds of therapy and rehab work to bounce back from it.

I can’t take it as well as I could when I was younger but that guy, that particular mask, it’s like a super hero outfit, putting on that outfit and putting on that mask, it’s got some special powers. It’s got some energy that I’ve summoned from another place in the sky somewhere and I’ve been able to put it inside of these masks and have it stay inside. It’s like a tribal thing, there’s been tribes all throughout the history of earth that have donned certain uniforms for doing certain things like hunting and healing, a spiritual energy, that is harnessed and trapped inside of the mask and it can only be used by someone who knows how to use it.

Well speaking of your mask, we kind of miss seeing it here in North America. Both Corey and Clown have hinted that there’s a U.S. tour in the works for this coming summer; can you confirm?

We’re going to be touring this summer in the United States, starting in June. I know February we’re supposed to be touring in Australia, that’s late February and into March, so we just keep adding things to the plate. Being that we’re older, it’s not quite as constant as it use to be, we use to tour relentlessly, where we’d only be home for a total of a couple of months out of a year. I’m definitely looking forward to the ‘Knot going out on the road and doing more shows starting next year for sure.

What about new music; I know there’s been different takes on whether or not there would be a new album. Is there anything you can tell us about that?

I know that everyone in the band is always writing music, whether it’s for Slipknot, their own satisfaction, or for a side project. I will say that the band has not been together writing music yet. We’ve not been together as a band to write music. If there’s any writing or recording going on, it’s happening by individuals and not as a group, which is kind of sad, but we deal with things how we can deal with them and try to move forward from there.

Yes, we’d be remiss not to talk about Paul and his passing. Obviously, it has had a large impact on the band. You wrote a song for Paul on your solo album, didn’t you?

Yeah I did, it’s called ‘Flat Lace’, I wrote it actually between five and six years before he died, and the song is about his death, like I predicted it.

So Paul actually had the opportunity to hear the song?

Yeah, I actually got to play it for him, that was big for me, to be able to share that with him. I’m a recovered junkie myself, there’s a lot of things that he and I could relate on and I was able to understand certain things that he was going through. I wrote the song just to kind of let him know that I understood what he was going through, and that I understood how he felt, and that I was here for him. That even though I, I don’t know, it’s just kind of a thing, you can never do the work for somebody with that, you can only let them know that you understand what they’re going through and that you’re there to support them if they try to pull themselves out of it.

I don’t know, there was just something inside of me that knew that he more than likely wouldn’t be able to pull himself out of it and that it would lead to his demise. I thought maybe if I wrote a song and could play it for him that it might help him find something to grab onto to fight it off but it is what it is. I’m just thankful that I was able to have that moment with him and share it with him.

Watch the Official Trailer for the 'Iowa 10th Anniversary Edition'

More From Loudwire