31 Years Ago: Pantera Release ‘Power Metal’

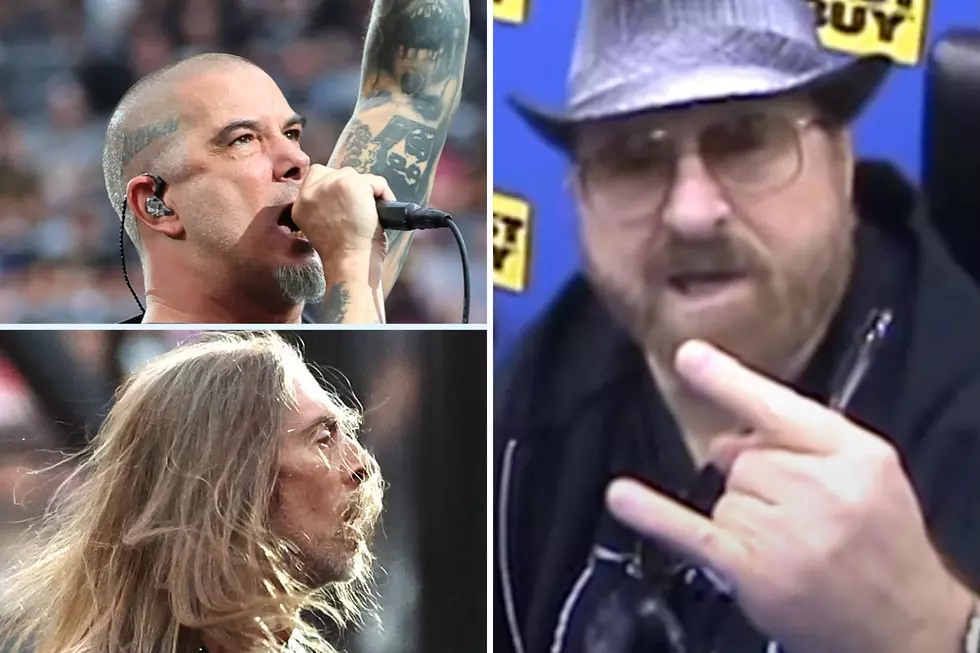

By the time Philip Anselmo auditioned for Pantera in 1986, the band had already self-released three glam-infused albums on Metal Magic Records. But even before they met Anselmo, guitarist Dimebag Darrell (known as Diamond Darrell at the time) and drummer Vinnie Paul were hungering for something a little heaver for album number four.

They had heard Metallica and Motörhead and realized there was a whole world of thrash to explore. And while they weren’t ready to dive into the mosh pit just yet, they found a middle ground, with songs rooted in the blazing, soaring music of Iron Maiden and Judas Priest. To the chagrin of their poodle-haired singer Terry Glaze, they crafted songs that replaced their flash and strut with crash and crunch. Finally, Glaze had enough and bailed and they invited Anselmo, who they had met on the road, to fly in from New Orleans to audition.

“We had a talk, and then I tried out with a bunch of Iron Maiden and Priest songs,” the singer recalled during a conversation in 2012. “I was real familiar with Priest. When I was a kid, I used to come home from school, put on Unleashed in the East and sing it note for f---ing note! I could hit all the high parts, I’m proud to say. So, we just jammed on this stuff, and then they played me some of their new demos, a lot of which became Power Metal; it was a lot more aggressive than their other stuff. I was like, ‘Wow you’re heading in the right direction.'”

While Anselmo saw promise in the band’s new direction, Pantera were stoked to hear a vocalist with a raw, multi-textured style who didn’t want to sound like Vince Neil. Only bassist Rex Brown, who was a big fan of glam metal, wasn’t immediately hooked, but he recognized Anselmo’s skill as a frontman.

“From the first time the guy walked in the door, we could just tell he had this aura,” Brown told me during a run to promote his 2013 book Official Truth: 101 Proof – The Inside Story of Pantera. “There was testosterone just f---ing flying. When he came in the fold, we rehearsed in Dime’s mom’s front living room with amps on 12 and there it was. I had a bottle of tequila and we smoked a joint and played every Judas Priest song we knew. There’s a lot of Priest on Power Metal. That was the one thing that Darrell and Phil immediately had in common.”

Pantera wrote most of Power Metal in 1986; the album was released in May/June of 1988 (Wikipedia lists the release date as June 24, 1988, on Pantera's discography page, but May 1988 on the Power Metal album page). The band recorded with country and blues producer Jerry Abbott (Dime and Vinnie’s dad) at his place, Pantego Sound Studio in Pantego, Texas, with additional production by Keel guitarist Marc Ferrari on the track “Proud To Be Loud.” It was the first time the band had used an outside writer and Abbott, who was managing his sons’ band, hoped “Proud to Be Loud,” a lunk-headed hybrid of KISS’ “Lick it Up” and Priest’s “You’ve Got Another Thing Comin',” would be the push Pantera needed to land them a major label record deal.

It wasn’t to be, but as a pure expression of aggressive energy, Power Metal showed Pantera to be more in touch with the times than they had been previously, and the record acted as a bridge between their chugging New Wave of British Heavy Metal-influenced sound and the more thrash and power-groove material that was to come with '90’s Cowboys From Hell. Numerous songs are reminiscent of Priest. “Rock the World” sounds kind of like early Manowar, and while “Over and Out” and the title track featured faster tempos and heavier riffs that brought the band’s sound closer to speed metal. The only real stinkers are the ballad “Hard Ride” and “P.S.T. 88,” a cheesy sex-charged cut with the awful vocal shout-out “p---y tight tonight.”

“Power Metal was a pure Power Metal record, you know?” Anselmo said. “To say I'm proud of it -- no, I'm not. But to say that we as a band were still trying to discover who the f--k we were and what we could do, that's very evident. S--t, I was in the band probably two weeks when all of a sudden, sure enough they got all these songs demoed that I had heard on my first visit, and I'm in the studio and they’re all, ‘Okay, come up with heavy metal lyrics right here on the spot, and let's just f---ing do it.’ I did the best I could, and I think they were heavier overall, more attacking, I guess. But it wasn’t the kind of thing I put my heart and soul into. I didn’t bleed for these songs like I did later in the band’s career.”

While Jerry Abbott had championed the music Pantera had written with vocalist Terry Glaze and sent it out to numerous record labels, at first he wasn’t so excited by his sons’ decision to make heavier, seemingly less accessible music. “There was definitely a time when the LD -- which is what Dimebag and Vinnie would call their father -- the Elden, like the Elder… You gotta remember this was Fort Worth, Texas. So anyway, the Elden was getting a little perplexed at the direction we were going in. It got to the point where he wasn't getting it anymore; it wasn't your standard rock song writing. We were on a f--king mission to tear throats out and he was eventually kind of phased out.”

Even so, Jerry Abbott was an important role model for his sons and even supported Anselmo, whose vocal style on Power Metal seemed to be guiding Pantera further away from the rock and roll that Abbott understood.

“He definitely helped me as a newcomer in the studio,” Anselmo said. “It was mind blowing back then and pretty intimidating for me to be recording an album. And sometimes it was overwhelming. Case in point: ‘We’ll Meet Again.’ I didn’t know what the f--- to do with the song because it didn’t feel right for me. So Darrell shows up and he goes, ‘Man, I got this tape. You gotta here it. The LD tracked some vocals on there to help you out.’ I'm like, ‘What! Dude, that’s a trip!’ It was insane! The Elden had laryngitis. So we're sitting there listening to that f---ing song, and here’s the LD with his voice cracking, high pitched and hoarse and s---. And I’ll be damned if he didn’t help get me through the track by building the foundation for that song.”

Jerry Abbott might not have understood the appeal of the Pantera’s more caustic music, but a record executive he had been trying to sell on the band for years, Derek Schulman, who would eventually sign Pantera to Atco/Elektra, was starting to understand Pantera’s market potential, and Power Metal was the turning point that convinced him to send one of his A&R men to check out Pantera live.

“I had listened to Pantera’s third self-produced album, when I was Sr. VP of A&R at Polygram and although I thought it a well-crafted, heavier album with fantastic playing by the band, it still did not have that unique quality that they would ultimately acquire,” Schulman told me in 2013. “It was not, at that time, particular distinctive from the artists that I was involved with, like Bon Jovi, Cinderella and Kingdom Come. Then their attorney Jules Kurz alerted me to their change sound in mid-1988. He showed me a VHS videotape of their new singer Philip Anselmo with a sampling of their new songs and I had to admit I was totally taken by surprise. It was very different from their old sound and watching Phil together with Darrell onstage on this tape was mesmerizing.”

Not all of the band’s fans were jazzed by Pantera’s new direction. The group had earned its stripes playing three shows a night at local bars. Mostly, the sets consisted of covers, but every now and then the band would throw in an original. Suddenly, they had more originals than covers and they were itching to share their new music with their audience. Needless to say, some of their kids who had banged their heads to covers of Scorpions, Ozzy and Ratt tunes, were as perplexed as Jerry Abbott, by the heavier material and more street-smart look.

Anselmo takes credit for the decision to drop the hairspray and tight pants. “I said, ‘Look here. No more spandex,'” he said. “We don't have to play their f---ing game anymore. We've turned the tables. We’re big now. What are they going to do, tell us NOT to play when the f---ing place is packed two times over?”

The rest of Pantera -- even Rex and Vinnie -- saw their singer’s logic. Some of the band’s older fans, however, were fighting mad. “One time I was headed to my hotel room and this mother---er was sitting out in the parking lot with his friends and he’s like, ‘Hey Phil, you keep playing that garbage s--t and you’ll opening up for my band one day.’ Those f---ers were lucky I was tired. When I was a kid, you didn’t yell that s--t and get away with it without walking away without blood coming from some part of your body.”

Some of the other local boys had the same attitude as their more loudmouthed peer. They didn’t appreciate Anselmo’s anti-glam aesthetic and many regulars stopped going to the band’s shows. For a while, Pantera were playing to smaller audience and worrying club owners who used to count them as a sure thing several nights a week. But soon a new crowd of thrash fans caught wind of Pantera’s new sound and flocked to the clubs to check out the cowboys from hell.

“We were very responsible in the Texas scene for changing the big bar, big glam bar mentality,” Anselmo proudly said. “We f---ing brought in more people, the pits began, the stage diving began and that brought in a whole different mindset for, I'd say 70 percent of the f---ing bars around there. That was the beginning of the big Texas overthrow right there.

“We just said, 'F--k off!' Once that f---ing spandex was shed, I could jump up on the mother---ing stage in the same clothes that I wore all f---ing day and sing the f---ing songs. That bred confidence and a new fire in our bellies, and next thing you know the rules were torn down; they burned. We were bringing in the crowds, not the club owners and promoters. And suddenly, kids are skanking, stage diving, and doing flips off the stage. Skinheads and punks started showing up and more underground people came in that wouldn’t go and see a more commercial band. To have won that victory felt like absolute liberation, the ultimate liberation and from then on it was a f---ing freedom for all.”

Loudwire contributor Jon Wiederhorn is the co-author of Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal, as well as the co-author of Scott Ian’s autobiography, I’m the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax, Al Jourgensen’s autobiography, Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen and the Agnostic Front book My Riot! Grit, Guts and Glory.

10 Reasons Why Pantera's Power Metal Is Better Than You Remember

More From Loudwire