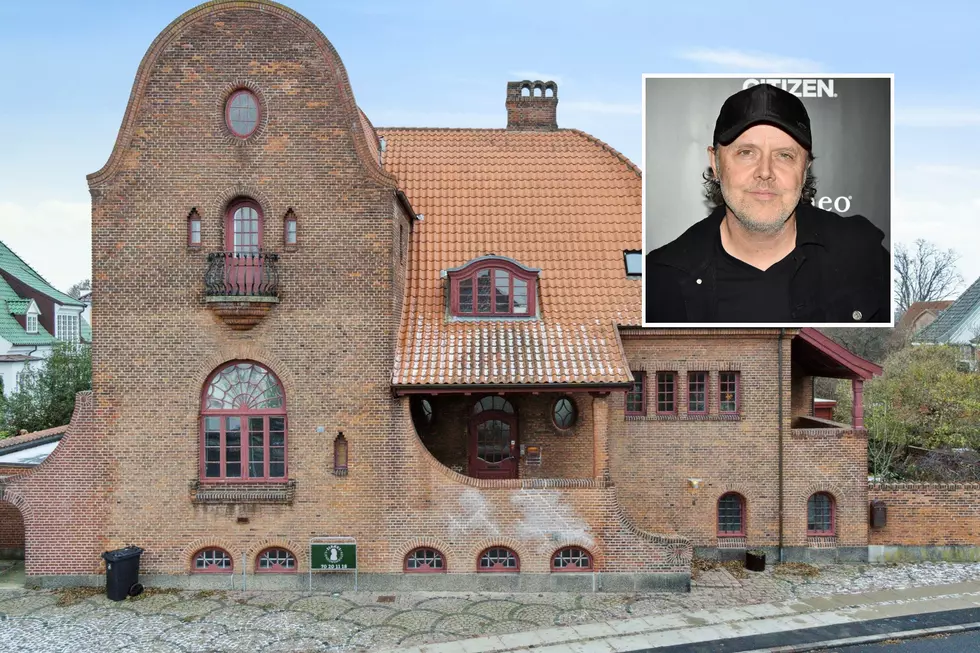

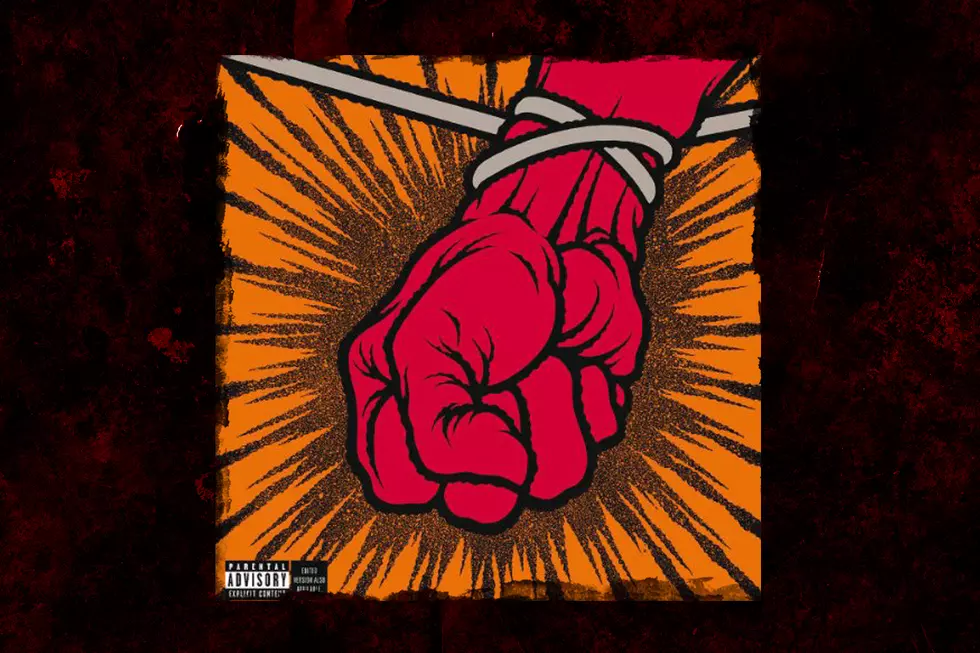

20 Years Ago: Metallica Release ‘St. Anger’ Amid Band Turmoil

Aside from 2011’s double-disc, Lulu, which Metallica collaborated on with Lou Reed, no album by the Bay Area thrash metal pioneers has been greeted with as much criticism and bewilderment as St. Anger, which was released on June 5, 2003.

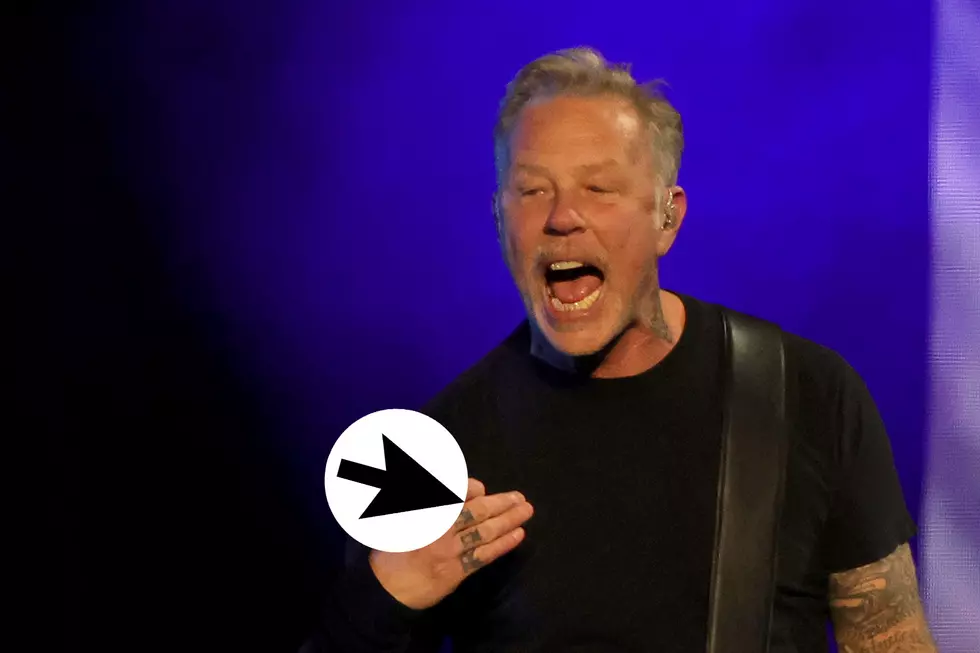

At the time, Metallica was going through a rough patch that left them on shaky ground. Frontman James Hetfield had just returned from a long stay in rehab and was feeling vulnerable and cranky so the band hired an eccentric musician’s therapist to help the members express their feelings and mend some tears in their relationships with one another. Since they hadn’t yet hired Robert Trujillo as their new bassist, their producer, Bob Rock, was filling in for the departed Jason Newsted.

It was a strange environment in which to record an album and it yielded a strange, raw, disjointed, low-fi release. I first heard St. Anger in April 2003 blasting through a stereo in an office at Elektra Records. At first, I thought the speakers were defective since the drums sounded tinny and echoey and the music was anything but polished. No, I was assured, This is exactly how the band wanted it to sound. It was only after sitting through the 75 minutes of music that I realized there was not one guitar solo on the record.

“So, they’re going to go back and dub in some extra guitars and leads before putting this out, right?” I asked the publicist at the label. Nope, what I was listening to was exactly what was going to hit the streets.

I was unsure what to make of what I had heard. The music was heavy and unrefined. Hetfield’s vocals weren’t especially clean and the songs weren’t conventionally structured. Even the vocals, which were abrasive and confessional, addressed Hetfield’s battle with booze, his dysfunctional childhood and control issues with his bandmates. But they did so in ways that were sometimes awkward; a lot of them seemed like they were spontaneous and delivered without much editing.

“Saint Anger around my neck, he never gets respect / Saint Anger around my neck / You flush it out, you flush it out / Saint Anger around my neck,” he sings in the title track. And on the appropriately titled “Frantic,” he roars, “Worn out on always being afraid / an endless stream of fear that I've made / You live it or lie it, you live it or lie it /

My lifestyle determines my death style / My lifestyle determines my death style.”

"It is jam-packed with energy, excitement, vulnerability, brokenness and intensity," Hetfield told MTV around the time of the album’s release. "It is an extremely meaningful record for all of us. It's a landmark. I think this is where we shed our old skins and really got down to the bones of Metallica."

Many fans didn’t agree. Despite going double-platinum, chat boards were packed with vicious comments about the album’s lack of cohesion, the absence of leads, the clattery drumming and the sometimes sophomoric lyrics.

Shortly after the album was released, guitarist Kirk Hammett said that St. Anger was not written to be accepted by the mainstream. It was an intensely personal project that Metallica needed to create in order to clean their palate.

“During our journey, we kind of forgot about this five-letter word called 'radio,'" Hammett told MTV. “And we are fine with that because we feel that this material is very strong and very representative of where we are now musically, personally, emotionally and mentally. It's the most complete band statement that we've ever made."

To date, everyone in the band maintains that St. Anger was definitely the album they needed to make at the time. And while Metallica don’t play songs from St. Anger in concert much anymore, they claim that the record was a missing link of sorts, the catalyst that allowed the band to transition from Load and ReLoad to Death Magnetic and Hardwired… To Self-Destruct.

For Metallica, the process of creating St. Anger was exciting in part because they didn’t have a plan when they gathered to make it. The riffs weren’t written in advance and there was no set agenda.

"For the first time, I had no idea where that ride was going to take us," Lars Ulrich told MTV. "The main thing for me was the ride has to be as pure as possible. James wanted everyone to start riffing from nothing and see where it would go — somebody taking the lead and somebody else following it in a very organic and collaborative way."

Sure, there were arguments and many moments of sheer frustration, as documented in the 2004 film by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, Some Kind of Monster. But there were also periods of kinship and cooperation. Hetfield, who had always been possessive over his music and lyrics, relented and actually reached out to his bandmates for help.

"That was the last indication that this really was a changed man [after he got out of rehab]," Ulrich said. "So, we took what we call the stream-of-consciousness process. It was almost like being at school with a pad and a pen. We all sat around and came up with ideas and then we'd go around the room and everyone would read to the class what they had come up with. It was somewhat intimidating in the beginning, but at the same time, incredibly challenging and an awesome thing to introduce in terms of just bringing everybody closer together."

Almost as interesting as the way the songs on St. Anger were written is the way they were recorded. Rock had created polished, pristine albums for Metallica, including 'The Black Album,' and also worked with Motley Crue, The Cult, Skid Row and Cher. In other words, the dude knows how to make albums sound good. In a way, he and Metallica intentionally made St. Anger sound, well, not so good.

"I wanted to do something to shake up radio and the way everything else sounds," Rock told me. “To me, this album sounds like four guys in a garage getting together and writing rock songs."

Metallica and Rock captured the primal sound and unfocused feel of St. Anger by blending old recording technology and digital editing hardware. On prior albums, Rock spent endless hours setting up Ulrich’s drums with various microphones and worked for up to a week perfecting Ulrich’s snare sound. In an effort to turn the tables on the band’s traditional tone, Rock spent “five minutes” miking the drums and recorded the rest of the band with a combination of high-tech mikes and cheap PA mikes. Then he blended the sounds together, giving most of the guitars on St. Anger a muddy, yet clear sound. Finally, he didn’t use ProTools to perfect anything and he didn’t make Hetfield sing take after take until he got the songs perfect.

"There was really no time to get amazing performances out of James," Rock said. "We liked the raw performances. And we didn't do what everyone does and what I've been guilty of for a long time, which is tuning vocals. We just did it, boom, and that was it."

At first, Metallica planned to add guitar solos to the disjointed songs. Hammett tracked a variety of leads, including slow, melodic passages and fluid, speedy runs. But in an era that downplayed guitar solos as self-indulgent and passe, Metallica decided they didn’t fit the songs and opted to leave them out.

"We made a promise to ourselves that we'd only keep stuff that had integrity," Rock said. "We didn't want to make a theatrical statement by adding overdubs. Every time we tried to do a solo, either it dated it slightly or took away from what we were trying to accomplish in some other way. I think we wanted all the aggression to come from the band rather than one player."

Once Metallica had recorded all of the songs on St. Anger, the band digitized everything and then reassembled song parts almost at random. “A lot of it was done in a William Burroughs cut-and-paste fashion," said Rock. “Some people use ProTools to trick and fool the listener, but we used it more as a creative tool to do something interesting and stretch boundaries.”

In the final analysis, Rock admitted that St. Anger is far from a perfect recording. It’s more like an art project that allowed Metallica to retain their core aesthetic of doing whatever it is they feel like doing at any particular point in time without concern for pleasing anyone but themselves. As such, there are odd sounds, unconventional arrangements and hardly as many choruses as fans had come to expect. As Rock explained, it wasn’t about following protocol.

"Technically, you'll hear cymbals go away and you'll hear bad edits,” he said. ”We wanted to disregard what everybody assumes records should be and throw out all the rules. I've spent 25 years learning how to do it the so-called right way. I didn't want to do that anymore."

Does that mean St. Anger is a good album? Well, it’s the record Metallica wanted to make. And it’s filled with interesting musical choices that are worthy of respect if not repeat plays. Moreover, there are some great, largely disregarded songs on the album. “Frantic” is a moshpit churner that, despite the arpeggios and vocal harmonies in the chorus, is driven by urgent guitars and a combination of thrash and groove drumming. And “Some Kind of Monster” is a doomy cut that builds in intensity with a riff that’s as solid as many in the Metallica canon and the eerie single note bends over the power-groove part of the song is harrowing. Finally, it’s pretty wild hearing Hetfield doing a damn good impersonation of Kurt Cobain when he moans, “I hide inside / I hurt inside / I hide inside, but I’ll show you” on the grunge-tinted “Invisible Kid.”

In retrospect, fans of 'The Black Album' and Load weren’t ready for the weird juxtapositions and low-fi savagery while thrash purists were miffed by the ragged recording, improvisational riffing and lack of solos. And pretty much everyone was surprised by some of Hetfield’s off-key vocal groans the record’s lack of cohesion and those clanging drums. But hey, Metallica always said St. Anger would be experimental, and experiments are meant to push boundaries and throw people off. Whether Metallica should have proudly released St. Anger or kept it as a personal pet project is another issue.

But fans who purchased the CD got more than just the most adventurous album in Metallica’s catalog. The disc came with a bonus CD of every album track being played live in rehearsal, as well as Internet codes that unlocked several old concert recordings that consumers could burn for free. All in all, that’s a lot of bang for the buck even if more is sometimes less.

Loudwire contributor Jon Wiederhorn is the author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends, co-author of Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal, as well as the co-author of Scott Ian’s autobiography, I’m the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax, and Al Jourgensen’s autobiography, Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen and the Agnostic Front book My Riot! Grit, Guts and Glory.

Every Metallica Song Ranked

More From Loudwire